Barts North Wing

A study in maroon and gold, among other colors

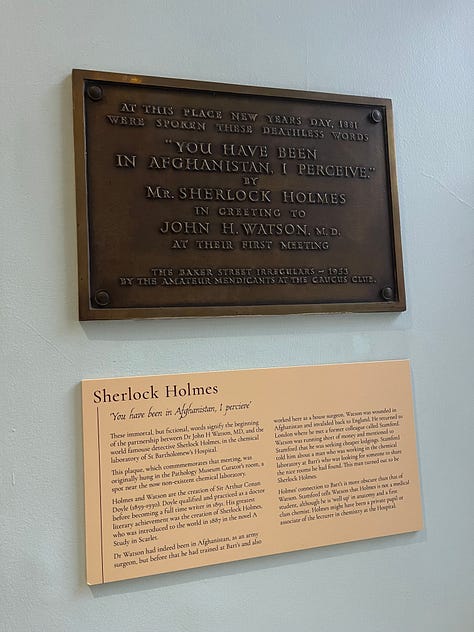

Possibly most famous as the initial meeting place of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson, St Bartholomew’s Hospital is the oldest continuously operating hospital in the UK.1

Barts

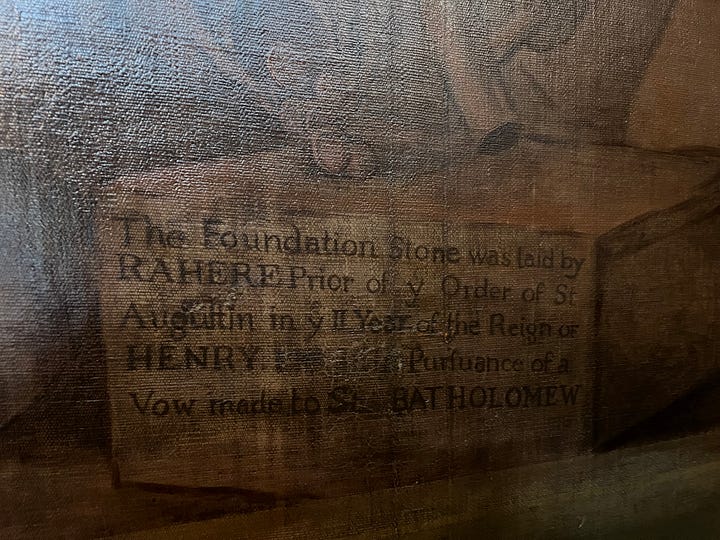

Barts was established as a hospital and priory in 1123 by Rahere, a courtier-turned-canon of otherwise unknown background.2 Per the few surviving contemporary records we have, on a pilgrimage to Rome, Rahere contracted an illness and promised God he’d found a hospital if he recovered.3

Unsurprisingly (given the topic of this piece), Rahere did in fact recover and, furthermore, had a vision of St Bartholomew on his journey back to England.4 The saint instructed him to build a church at Smithfield, then a suburb of the city of London.5 The hospital, built after the church, opened in March 1123.6

Henry VIII and Barts

In 1539, Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries was in full swing, and the priory at Barts was closed.7 The hospital remained open, but its property was confiscated and services were reduced.8 Due to its lack of assets and income, Barts was in dire straits.9

Henry VIII reestablished the hospital in 1546 after public uproar, instituting an administrative Board of Governors to run it.10 Additionally, in 1547, he granted the hospital property with which it could generate an income.11

The hospital, once again financially solvent, also took donations from this point onward.12

Gibbs’ rebuilding

By the 1700s, Barts had outgrown its medieval buildings, which were in poor condition even though they’d (barely) escaped the Great Fire in 1666.13 Hospital governor James Gibbs, a Scottish architect, proposed a new design for Barts’ rebuilding: four separate wings centered around a central courtyard.14 The separation of the four buildings would prevent both fire and disease from spreading between them, as well as allow for fundraising to continue as buildings were constructed one by one.15

The North Wing

The North Wing, opened in 1734, was the first of the four wings to be completed.16 It was designed as an administrative and ceremonial building, containing offices and a great hall, and built first in order to “attract and impress potential benefactors.”17

The building has remained relatively unchanged (given the complete demolition and rebuilding of others on the site) ever since, aside from the replacement of its original Bath stone cladding with Portland stone in the 1850s.18 Barts was funded by donation until 1948, at which point the newly-established National Health Service took over.19

The Hogarth Stair

The formal entryway to the North Wing, known as the Hogarth Stair, contains two massive history paintings by – you guessed it – William Hogarth, a painter and hospital governor.20

The story goes that, initially, some Italian painters were considered for the task of painting the entryway, but Hogarth offered his services free of charge and painted his first large-scale history paintings for the project.21 It’s possible he argued that an English painter should be prioritized for a charitable project such as this, but I couldn’t find any solid information one way or another.

As you enter the building, his painting Good Samaritan is immediately visible, and, as you turn the corner to go up the stairs, you then see his Christ at the Pool of Bethesda. Both paintings represent concepts central to the ethos of a hospital: Good Samaritan the treatment of all people, and Bethesda the healing of the sick.

It cannot be emphasized enough how enormous these paintings are. They confront (and almost overwhelm) the viewer with the importance of healthcare (emphasis on the care) and the diversity of people that need it. In sum, an excellent push for those benefactors to throw a few extra shillings towards the hospital.

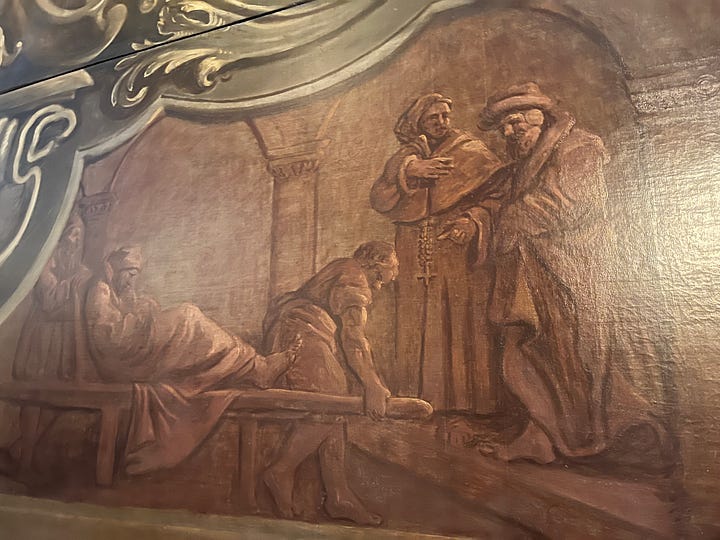

Below Good Samaritan are three cartouches depicting Rahere’s vision, the foundation of the hospital, and monks tending to the sick.

The Great Hall

At the top of the Hogarth Stair is a grand entrance to the Great Hall.

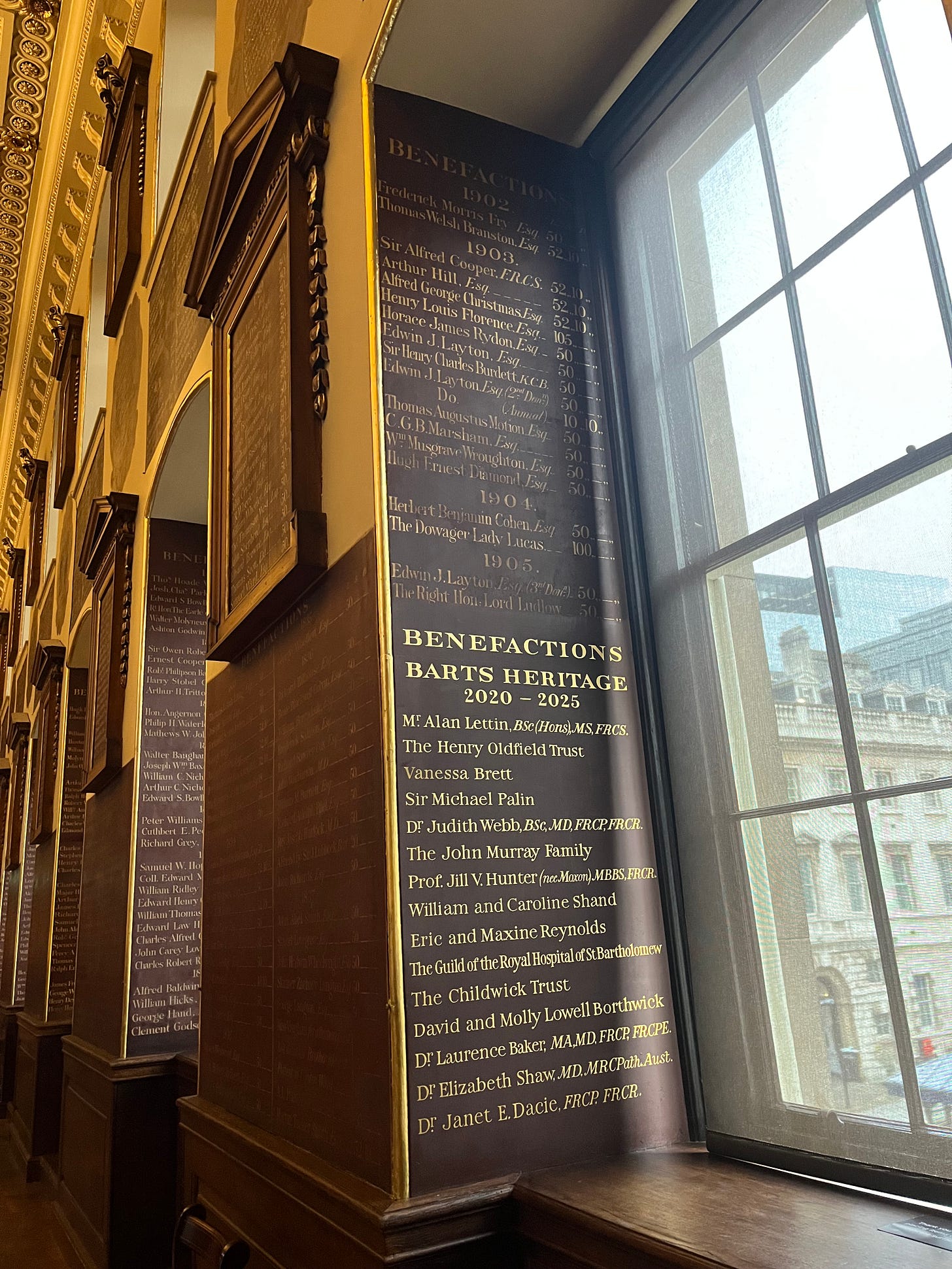

The genius of the Great Hall is in the names inscribed all over its walls – donors to the hospital from 1546 through to the modern day.22 The last donation recorded on the walls prior to the North Wing’s restoration work was in 1905.23 Names crisscross the walls over and over again – it’s surprising there’s any blank wall left with how many people are represented.

Retired orthopedic surgeon Alan Lettin, who consulted at Barts for 18 years, was the first donor to the North Wing’s restoration campaign honored with a new inscription in the Hall in 2022.24

There are a variety of other fascinating details present, including a 17th century stained glass window, an elaborate gilded plaster ceiling, three fireplaces, and portraits of Henry VIII, St Bartholomew, and Edward VII. In the interest of brevity, I will not be going into much (if any) depth on these, but I highly recommend taking a look at my photos of these elements of the Hall below.

The Great Hall was and still is used for hospital (and, these days, non-hospital) events.25 Medical school exams, fundraising dinners, governors’ meetings, and more have all happened in this room. But, until October 6, 2025, none of the North Wing was a publicly accessible space.26

Conservation and restoration

By the 2010s, the North Wing had deteriorated significantly.27 A new organization, called Barts Heritage, was established to support necessary restoration and conservation work in order to preserve the building for the future.28

The work took place over the course of two years (2023 – 2025),29 and it included external repairs, window resealing, repainting, re-gilding, internal repairs, polishing, and more.30 The Hogarth paintings were conserved, as was the stained glass Charter Window.31

In addition, an engagement team designed materials and activities for the public to access during visits to the site.32 Some are game-like and can be accessed at a stand in the Great Hall, and others are informative paddles present around the site with extra details on the building and the people involved in its construction.

In another room near the Great Hall, a nine minute video on the restoration efforts plays on loop. In it, various people involved in the project discuss their work, and there are also close-ups of disassembled pieces of the building from during the conservation process. If you’re visiting – it is not to be missed.

Miscellany

In a handwave towards concision, what follows is a brief overview of other publicly accessible parts of Barts that I visited and think are worth visiting, but don’t have the space to discuss in depth.

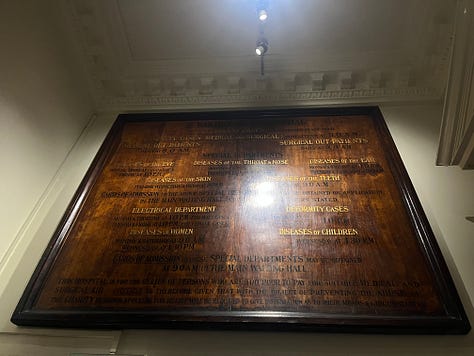

Hidden in the side of the archway underneath the North Wing is a museum on the history of Barts as a whole. It’s worth seeing for its giant old sign advertising various medical services and bizarre introductory video narrated by a fictional medieval monk. It also has a plaque commemorating Holmes and Watson’s first meeting, which was donated by Sherlock Holmes fans to the hospital.

Just across a path from the North Wing is the church of St Bartholomew the Less, the tower and west wall of which are the only remaining medieval structures in the Barts complex. Inside are memorials to various hospital figures and beautiful stained glass commemorating doctors and nurses from the hospital that died in World War II.

The courtyard between the four main wings of Barts has four covered seating areas with photos related to the hospital from various periods of history, as well as a fountain. It seemed like a nice place to sit for a moment and rest, though I didn’t spend much time in it.

Location details

Barts North Wing

North Wing

St Bartholomew’s Hospital

W Smithfield

London EC1A 2BE

Open Monday, Tuesday, first Sunday of every month 10am – 4pm

https://bartsnorthwing.org.uk/

“History and restoration,” Barts North Wing, Barts Heritage, accessed January 27, 2026, https://bartsnorthwing.org.uk/history-and-restoration/.

Judith Etherton, “Rahere [Rayer] (d. 1143x5), founder of St Bartholomew's Hospital and priory, London,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/23012.

Etherton, “Rahere.”

Etherton, “Rahere.”

Etherton, “Rahere.”

Etherton, “Rahere.”

Colin Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London: Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England, 1992, https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/8889/StBartholomewsHospitalLondonRoyalCommissionontheHistoricMonumentsofEnglandReport.

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

“St Bartholomew’s Hospital: Our history,” Barts Health NHS Trust, accessed January 27, 2026, https://www.bartshealth.nhs.uk/st-bartholomews-our-history/.

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Barts Health, “Our history.”

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

“Gibbs build,” The North Wing building, Barts North Wing self-guided tour, accessed January 26, 2026, https://bartsnorthwing.org.uk/tours/self-guided-tour/.

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Thom, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Andrew Greasley, “First new donor name in 100 years unveiled in the Great Hall,” News from St Bartholomew’s, Barts Health NHS Trust, January 26, 2022, https://www.bartshealth.nhs.uk/news-from-st-bartholomews/first-new-donor-name-in-100-years-unveiled-in-the-great-hall-12490/.

Greasley, “New donor name.”

Greasley, “New donor name.”

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

“The Barts North Wing launch – media coverage,” Barts North Wing, Barts Heritage, last modified November 17, 2025, https://bartsnorthwing.org.uk/the-barts-north-wing-launch-media-coverage/.

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

Barts North Wing, “History and restoration.”

“About Barts North Wing – our work and our team,” Barts North Wing, Barts Heritage, accessed January 27, 2026, https://bartsnorthwing.org.uk/about/.

Barts North Wing, “About.”

Barts North Wing, “About.”